Launch Statement

Promoting a people-centred aid system: IMPACT’s commitment to producing community-driven evidence for humanitarian decision making

In recent years, there has been growing momentum around putting people and communities at the centre of humanitarian action, packaged under a series of Accountability to Affected People (AAP) principles and commitments. This push for stronger accountability mechanisms and participatory approaches to aid action stemmed from serious concerns around the behaviour of humanitarian actors, including abuse and corruption, as well as perceptions of paternalism, neocolonialism, and generally ineffective aid interventions that were designed without the input of communities.

At the same time, more efforts and resources have been put into enabling evidence-based and data-driven humanitarian response planning, with inter-agency initiatives like the Joint Inter-Sectoral Analysis Framework (JIAF) seeking to deliver on a system-wide approach for integrating data and analysis into annual planning exercises. The aim here has been to ensure decisions around resource allocation and the prioritisation of particular crises, population groups, or geographic areas are taken based on where the evidence shows needs are greatest.

While the humanitarian sector has made enormous progress on measuring the severity of needs within and across crises – including through implementing Multi-Sector Needs Assessments in major emergencies – there remains an insufficient focus at inter-agency level on developing frameworks to jointly solicit, analyse, and use community inputs on what people actually want. This is one of the key blocking points when it comes to achieving genuinely people-centred humanitarian action.

A major rethink is also needed around the research and assessment methods that aid actors currently rely on to understand the needs and priorities of crisis-affected people – both in terms of capturing people’s own expression of their needs, preferences, and priorities more effectively, as well as ensuring that the voices of marginalized groups are taken into account.

In light of these ongoing gaps and challenges, at IMPACT, we are looking inwards and taking stock of how to tackle questions of accountability and inclusion in humanitarian response planning and decision making. We also aim to pinpoint how our methods can be improved, pilot new approaches that better respond to these concerns, and scale up approaches that successfully address them. Developed through our flagship initiative, REACH, our global strategy on Accountability & Inclusion consists of three pillars:

1. Enabling demand-driven humanitarian assistance

2. Enabling inclusive and safe humanitarian assistance

3. Implementing accountable and inclusive research practices

As the REACH team rolls out this strategy, our new Accountability & Inclusion thread will share insights and reflections from our teams across 30+ crisis contexts, including lessons from the field as they test out new people-centred approaches, key findings from A&I research workstreams, and data-driven perspectives on ongoing humanitarian reform discussions.

We hope you follow along for new posts and updates, to learn with us along the way.

12/01/2024 – Global – A more accountable humanitarian response is built on reliable, independent data

The 2024 Global Humanitarian Overview estimates nearly 300 million people around the world will need humanitarian assistance over the coming year. Meeting this scale of need with an adequate response will require more than 46 billion USD. At the same time, financial pressures on the international system are leading to funding gaps, as crises grow more protracted, the average length of displacement grows longer, and conflict, climate-related disasters, and other drivers of crisis intensify.

As the global community looks ahead to another challenging year, at REACH we are also considering how to measure and understand the scope and severity of needs, and ultimately make better decisions about how to prioritise when aid budgets are being stretched. To that end, we offer some reflections on the continued importance of accurate, crisis-wide data to enable fair and impartial allocation of humanitarian assistance between and within crises, and avenues to adapt existing assessment models to support more people-centred humanitarian planning.

Where we are now, after two decades of reform.

Over the past two decades, successive rounds of humanitarian reforms have led to major gains in making humanitarian assistance more effective and predictable, including through enhanced response protocols, planning processes and quality standards.

But nearly ten years after the Grand Bargain, many actors now point out that these reforms have inadvertently led to inefficiencies in the timely provision of assistance, by contributing to a sprawling bureaucracy around humanitarian prioritisation and planning.

This observation has led many in the field of humanitarian data to reflect on the role of joint needs assessments in making the Humanitarian Programme Cycle more burdensome. As REACH, we have had a front row seat to instances where the level of effort and resources put into implementing these assessments was not proportionate to the impact on decision-making.

This problem requires a thorough exploration of deeply entrenched issues that get in the way of transparent and evidence-based decision making, and that extend far beyond assessments per se, including mandate wars and the politicisation of aid. At the same time, we must not lose sight of the fundamental reasons why joint needs assessments were such a central component of the Grand Bargain to begin with, and ensure that we don’t backtrack on the progress made towards generating robust evidence in humanitarian settings.

More than ever, accuracy matters.

In a context of increasing pressures on humanitarian financing due to spiralling needs, it is more important than ever to establish clear parameters for the fair and impartial prioritisation of humanitarian assistance, and ensure that these parameters are supported by robust and comparable evidence.

Over the past decade, REACH has developed a robust model for crisis-wide and methodologically sound annual assessments of the severity of humanitarian conditions and living standards gaps in crisis-affected areas, known as the Multi-Sector Needs Assessment (MSNA). These assessments have been implemented in over 30 humanitarian contexts globally, and in many cases over multiple consecutive years.

In highly dynamic crisis contexts where basic statistics on human living conditions are either unavailable or rapidly outdated, humanitarian needs assessments often provide the closest thing that we have to a quantitative measurement of potentially life-threatening deprivation of resources and rights.

The data from consecutive MSNAs, when considered longitudinally, also provide a starting point for humanitarian and development actors to look honestly at the outcome of their work, in terms of real-life improvements in access to clean water, food or adequate shelter, in places where they implement programmes.

These assessments also allow humanitarian actors to collect representative views and perceptions from tens of thousands of affected people, about their priorities and preferences. By ensuring that data on humanitarian needs is not only generated by actors that have a direct stake in the response, impartial needs assessments count among the few real safeguards that the humanitarian system has in place against politically-driven prioritisation, self-interested narratives and supply-driven planning by humanitarian agencies, and therefore should be seen as an accountability mechanism in and of itself.

| Impartial needs assessments count among the few real safeguards that the humanitarian system has in place against politically-driven prioritisation, self-interested narratives and supply-driven planning by humanitarian agencies, and therefore should be seen as an accountability mechanism in and of itself.

|

People’s lives are complex and multifaceted. Quantitative surveys can’t tell the whole story.

For all of the above reasons, MSNAs and other quantitative surveys will continue to be relevant in humanitarian responses going forward. In a context of shrinking resources relative to level of need, it is vital to ensure that accurate and comparable measurements of severity and self-reported priorities are available, enabling informed allocation decisions between crisis-affected countries, within crisis-affected countries, and between sectoral priorities.

That being said, these predominantly quantitative crisis-wide assessments were never intended to provide all of the answers. Crucial decision-making on the what, who, where and how of aid delivery should be based on multiple sources of information. Thus there is space to give greater attention to qualitative or unstructured data, especially when it comes to complex issues, in the field of protection, for example, or data on perceptions.

Currently, the system places an outsized focus on quantitative measurements, often at the expense of developing better systems that would allow us to meaningfully take into consideration qualitative inputs, testimonies or other forms of unstructured data when making decisions at the strategic level. Most critically, when it comes to actual planning decisions, direct participation and localised exploration of community priorities and needs is absolutely the way forward for the humanitarian sector.

REACH, like other humanitarian research actors, is in the process of rethinking the essential pieces of evidence that must complement – and balance out – quantitative crisis-wide assessments. To do so, we are investing in research methods that are more participatory and consultative in nature and that incorporate a stronger focus on self-reported priorities and perceptions in their research questions.

We are also reflecting on the limitations of our position as an international research actor in a system that continues to relegate local actors to the periphery of decision-making, and conscious that any future humanitarian reform efforts should include commitments toward locally-led research so that this work takes place in support of – rather than in lieu of – a locally-set research agenda. We, along with others, don’t have easy answers to some of these questions, but we are committed to learning and improving as we go.

18/12/2023 – Global – “Tell us what you need” – making sense of perception data and its role in humanitarian decision-making

In recent years, humanitarian research has increasingly recognised the importance of asking affected communities to define their needs and priorities in their own terms, rather than solely trying to measure objective needs on behalf of populations by using a set of technical indicators. Loosely termed ‘perception data’, the gathering of self-reported needs has rightfully gained much traction in humanitarian discourse, reflecting a growing awareness of the need to better integrate community views into decision-making. However, the extent to which this is meaningfully happening remains extremely limited, and whilst self-reported priorities are increasingly included in planning documents such as the Humanitarian Needs Overview, there is little evidence that these views have a direct impact on the where, what and who of aid programming decisions.

How should we gather information from affected communities about their priorities and preferences? How can we make sense of this information when it doesn’t align to other, more technical measurements of need? And how do we better integrate this data alongside standard needs assessment findings to provide clear recommendations for decision-making?

2023 MSNA Data Collection – Ukraine

These are questions that we are wrestling with as a humanitarian research agency, looking inwards at the quality and ethics of our work, and outwards at how this work is being utilised by our partners. A recent learning paper produced by our global Accountability and Inclusion team compared two sources of perception data in Somalia to illustrate the complexity of collecting self-reported needs, demonstrating that even the way in which we ask the question can produce very different results. Whilst data from our annual Multi-Sector Needs Assessment (MSNA) pointed to food, shelter and healthcare as community priorities, asking an open-ended question on needs via a radio debate yielded answers on peace and security and community action.

As the paper outlines, both sources of data have methodological merit, but both also raise questions about how we as a humanitarian community should respond. We identified three ways in which the sector can improve on this front:

- Better understanding of the perception data we collect: Rather than looking for the ‘one objective truth’ on the needs of affected populations, we should be putting more time into contextualising the perception data we are collecting.

- Stronger commitment to prioritise perception data in decision-making: If humanitarian programming is to be more effective at responding to the self-reported needs of communities, then we must find ways to better integrate perception data into our planning processes, rather than treating it as a stand-alone piece of evidence.

- More joined up working to respond to needs in a comprehensive manner: affected communities don’t categorise their needs into ‘WASH’, ‘shelter’ or ‘protection’ – placing self-reported priorities at the centre of decision-making therefore forces us to think beyond the confines of humanitarian service delivery, encouraging more joined-up working across agencies with different mandates, and between international and national actors.

WHAT CAN WE DO AS IMPACT?

As a research agency which aims to provide evidence to support more effective humanitarian action, we have a responsibility to help shift the dial on how perception data is used in decision-making, recognising that asking affected communities to define their own needs has value from both a data quality and a moral standpoint. In real terms this means:

- Strengthening our qualitative data methods to better understand the self-reported needs and priorities of affected populations, and then working with local organisations and community representatives to contextualise that data so that it is actionable for humanitarian decision-makers.

- Fundraising for work that focuses on qualitative data alongside quantitative, and that carves out space for research and development to understand how populations’ preferences and priorities can be more systematically included in analytical frameworks designed to measure humanitarian need.

- Relatedly, producing analysis that places value on perception data alongside technical measurements of need, and presenting both data sources to decision-makers in a more nuanced and thoughtful way.

Read the full learning paper here for a more in-depth look at how our understanding of perception data is evolving. This piece is part of a wider internal workstream being led by our global Accountability and Inclusion team to better understand people-centred research and what it means for IMPACT.

24/11/2023 – South Sudan – “The body does not carry the name”: community perspectives on displacement, humanitarian categorisation, and durable solutions

Photo: ICRC/MACKENZIE KNOWLES-COURSIN,

In South Sudan, displacement is extensive, damaging, and ongoing after a decade of conflict and natural disasters. As of June 2023, roughly 2.4 million South Sudanese refugees are displaced globally, and a further 2.2 million South Sudanese are internally displaced, with internally displaced people (IDPs) present in all 79 counties. Displacement has divided families, disrupted livelihood opportunities, interrupted education, strained resources, and has at times fuelled tensions between communities.

Efforts by government and aid actors to identify and implement solutions to South Sudan’s displacement crisis must align with affected people’s rights, needs, and preferences, in order to ensure these solutions are effective and lasting. This includes involving not only IDPs, but returnees and host community members as well, who are all affected by displacement. To support key stakeholders in this endeavour, REACH conducted an assessment to inform durable solutions programming from a community-centred and conflict-sensitive lens. With support from Conflict Sensitivity Resource Facility, Danish Refugee Council, and the Regional Durable Solutions Secretariat, a qualitative approach was taken, consisting of 48 focus group discussions, 28 key informant interviews, and 22 individual interviews with displacement-affected communities in Juba, Jur River, Nimule and Wau.

The title of the report, “The body does not carry the name,” is a quote from a resident of Nimule who expressed frustration by being labelled an internally displaced person – despite having lived in his community for many years. His words point to the risks associated with categorising people and communities – as IDPs, returnees, refugees, or host communities – in the course of humanitarian programming. While such labels are often necessary to humanitarian work, they can conflict with communities’ own views of themselves, and risk reinforcing divisions. This research sought to explore how communities in South Sudan perceive these labels, what they mean, when they apply, and when they may cease to apply – which is a critical starting point to any conversation on durable solutions.

While participants shared distinct perspectives on when IDP status ends, the most-cited factors were self-reliance and access to land, living peacefully amongst the host community, and returning to where one originally came from. Access to land was often associated with the ability to cultivate crops, build shelters, and achieve self-reliance.

“When I have established myself in the community and no longer depend on humanitarian assistance, then I do not need to be called an IDP.“

– Key informant in Juba

In several interviews, participants reported that humanitarian assistance accentuated divisions between groups. Some participants said that this manifested through chiefs not distributing assistance to people who were not originally from the area, thus reinforcing the non-recipients’ perceptions that they were not treated equally, while others saw dependence on assistance as a marker that one was an IDP.

In Juba, Jur River, and Wau, living amongst the host community (and, where relevant, leaving the IDP site) was seen as a necessary step towards ending one’s IDP status. This is an important reminder that, while encampment may be necessary in the short term, such as in situations of insecurity, providing people with the means to leave the camp in safety and dignity is essential if durable solutions are to be found.

Several participants also suggested that the passage of time was relevant to ending IDP status; however, suggested lengths of time varied greatly, and simply being in a place for a given amount of time was generally seen as insufficient. Rather, time was considered relevant if it provided people with the opportunity to access land, increase their self-reliance, or establish relations with the host community.

“If you’re staying with the nearby people in peace for a long period of 3+ years, maybe they will see your behaviour and you could buy a land, and nobody would call you an IDP.”

– Male host community member, Nimule

While safety and security are necessary preconditions to durable solutions for the millions of displaced South Sudanese citizens, they are not sufficient. Assessment participants commonly stressed the importance of accessing resources, particularly those that enable self-sustaining livelihoods, as necessary for sustainable integration. In Nimule, one participant expanded upon the concept of peace, stating:

“Peace is not just the absence of war. It’s when there’s food on the table, when kids are going to school, when police can’t beat you for no reason, when violence isn’t committed… Right now, there’s no peace, no school, no health facilities. People are still there [in the area of origin] because there are NGOs there. But there are places that they can’t reach.”

Assessment findings indicate that access to services, particularly education and healthcare, also play a significant role in decision-making regarding whether to remain or migrate. The availability of services in different locations can lead to family separation, as households try to balance risks and opportunities in different areas. Given that disparities in services are more linked to geographic location than to population group, area-based approaches to durable solutions are likely to be more effective than approaches based on population groups as a whole.

Read the full report for more analysis of the findings.

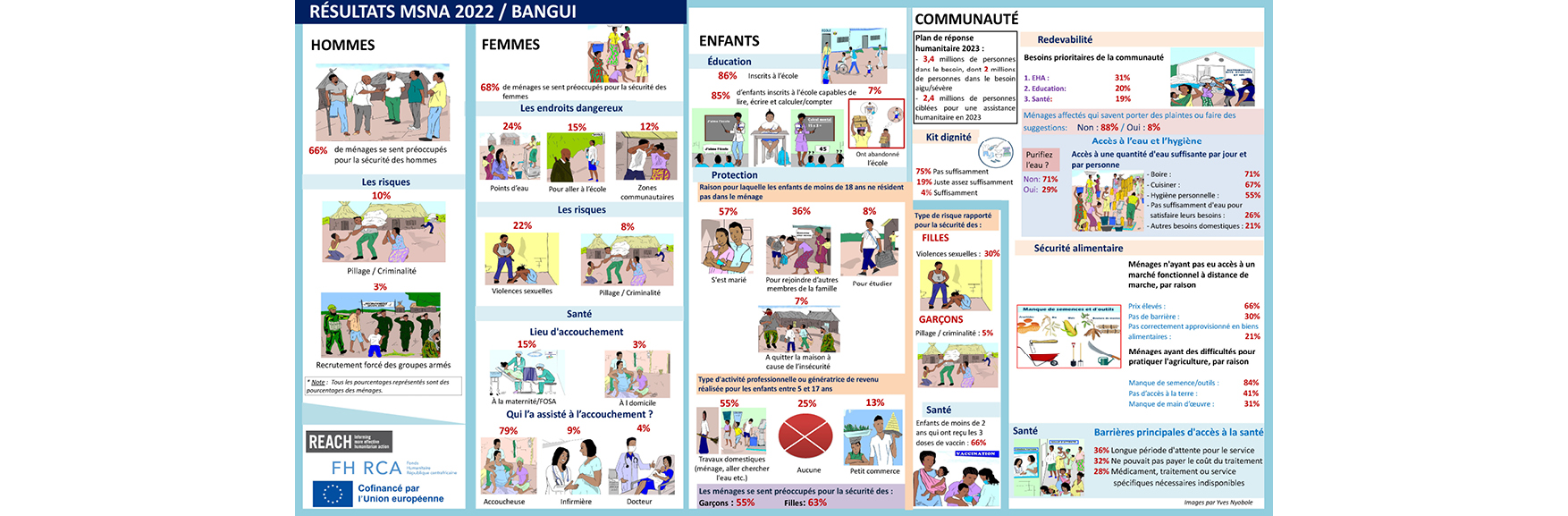

16/11/2023 – Central African Republic – Presenting MSNA results to local communities through different methods: Posters, radio broadcasts, and direct outreach

(English version below)

Pour la deuxième année à REACH, des posters présentant les résultats des Evaluation multisectorielle des besoins (MSNA) ont été créés en République Centrafricaine (RCA), afin de communiquer les résultats clés à la population affectées par la crise. Cette initiative s’inscrit dans un plus grand effort d’impliquer les communautés locales dans la dissémination des conclusions de nos recherches, afin de renforcer notre engagement communautaire et améliorer la redevabilité dans nos activités.

Nous avons interrogé Aysha Valery (Senior Assessment Officer en RCA), qui a soutenu ce projet :

- D’où est venue l’idée de créer ces posters ? Quel était leur objectif ?

2023 est la 5ème année consécutive qu’IMPACT – à travers son initiative REACH – effectue la MSNA en RCA. Pendant nos anciennes évaluations, nous avons souvent eu comme retour des communautés que REACH est présent chaque année pour mener des enquêtes, mais sans leur en donner les résultats.

Dès 2021, nous avons donc commencé à aller dans les régions où nous avions effectué des enquêtes auprès des ménages, afin de communiquer les résultats clés des MSNA à la population au moyen de posters, avec l’objectif d’utiliser des images pour en faciliter la compréhension – en particulier pour ceux qui ne savent pas lire – avec l’objectif de toucher toutes les couches de la population.

Les images attirent plus l’attention qu’une longue présentation avec des chiffres et de la terminologie humanitaire, qui sont souvent difficile à comprendre pour la population, dont la plupart pourrait ne pas être en mesure de lire et d’écrire dans la langue prédominante.

Qui les a créés, et quel a été le processus ?

Les posters ont été créés par l’équipe MSNA, qui comprend les chargés d’évaluation, les chargés de terrain et la coordination. D’abord, nous avons discuté pour choisir les indicateurs qui parlent le plus aux expériences de la population. La participation des chargés de terrain était essentielle dans ce processus car ce sont eux qui supervisent les enquêtes et la collecte des données, et qui ont donc la meilleure connaissance des communautés que nous visitons. Après avoir sélectionné les indicateurs, nous avons discuté avec un dessinateur centrafricain, recommandé par le groupe de travail “Accountability to Affected People” (co-dirigé par UNICEFF et OCHA), qui a ensuite crée des images des indicateurs, facilement compréhensibles pour la population.

Comment les posters ont été disséminés aux communautés ?

L’équipe MSNA, avec la consultation d’OCHA, s’est mis d’accord sur les localités à visiter pour disséminer les résultats de la MSNA 2022, qui ont été Kaga Bandoro, Berberati et Bangui. Chaque année, REACH essaie de visiter des nouvelles communautés pour accéder à de populations qui n’ont pas encore été touchées. Cela représente aussi pour nous une opportunité de sensibiliser la population à ce qu’est la MSNA et assurer leur coopération.

Avec le même objectif et en plus des posters, nous avions établit une collaboration avec des radios communautaires pour des émissions en direct où les personnes ont la possibilité d’appeler pour poser des questions ou interagir. L’émission est alors rediffusée dans d’autres relais communautaire. Les stations de radio ont également organisé des clubs d’écoute après les émissions, qui sont des groupes de discussion avec des membres de la communauté qui sont enregistrés avec la station de radio. Pendant ces sessions, les posters sont présentés et animés par les chargés de terrain, et sont ensuite remis à la mairie de la communauté pour une plus large diffusion. Nous avions aussi imprimé des petits posters pour distribuer aux participants des clubs d’écoute afin qu’ils prennent le relai pour disséminer les résultats dans leurs communautés respectives.

Quelles étaient les informations importantes à communiquer à propos des MSNA ?

Il était important de leur expliquer ce que c’est la MSNA, pourquoi nous l’effectuons, les résultats clés et ce qui est fait ensuite avec ces données. Sur le dernier point, nous avons collaboré avec OCHA qui a partagé comment sont utilisées les données MSNA pour planifier la réponse humanitaire.

Quelles ont été les réactions et retours ? Y a-t-il eu d’autres idées similaires pour communiquer ou échanger avec les communautés affectées ?

Les réactions étaient largement positives. Les membres de la communauté ont exprimé leur reconnaissance que REACH ait pris le temps de discuter les résultats avec eux. Ils ont également demandé à faire la dissémination auprès des autorités locales et des membres de la communauté directement, au lieu de à le faire faire à travers les clubs d’écoute.

En ce qui concerne les MSNA 2023 et la dissémination de posters, quels sont les résultats marquants de cette année ?

Après une analyse préliminaire des données, certains résultats clés sont :

- La situation sécuritaire semble s’améliorer, à l’exception de la zone de sud-est où nous avons vu une augmentation d’activité de groupes armés.

- Dans beaucoup de domaines, comme l’accès à l’eau, aux latrines, aux services de santé et aux services de protection, les PDI (personnes déplacées à l’intérieur de leur pays) en site ou lieu de regroupement semblent être mieux placé par rapport aux autres groupes de population dû à la concentration des acteurs humanitaires sur les sites. La population retournée a beaucoup augmenté dans la première moitié de l’année selon les données de Displacement Tracking Matrix de l’IOM. Récemment arrivés dans leurs localités d’origine, ils ont besoin de plus de support pour reconstruire leurs vies.

- En ce qui concerne la mortalité, 1 préfecture sur 16 a affiché des taux de mortalité bruts élevés dépassant les seuils d’urgence de l’OMS au cours de l’année 2023. Six autres préfectures sur 16 ont affiché des taux de mortalité élevés susceptibles de dépasser les seuils d’urgence sur la base de leurs intervalles de confiance.

- Concernant la sécurité alimentaire, la situation est critique. 50% de ménages ont un score de consommation alimentaire pauvre ou limite, et la majorité de ménages utilisent des stratégies de survie de crise ou d’urgence pour faire face à un manque de nourriture (selon le Livelihoods Coping Strategies Index).

- Les personnes en situation d’handicap et les personnes âgées semblent avoir le moins d’accès aux services de base comme eau, latrines, santé et marchés.

Les résultats des MSNA 2023 seront bientôt partagés, avec plus de détails sur ces différents chiffres. Cette année également, des posters seront créés pour les partager avec la population.

Tous les posters de l’année dernière, par région, se trouvent ci-dessous :

- Bangui

- Bangassou

- Bambari

- Ouaka PDI site

- Haute Kotto PDI site

- Kaga Bandoro

- Bria

- Berberati

- Nana Gribizi PDI site

_______________________________________

(English version)

For the second time at REACH, posters presenting the results of the Multi-Sectoral Needs Assessment (MSNA) have been created in the Central African Republic (CAR), to communicate key findings to crisis-affected people. This initiative is part of a wider effort to engage local communities in the dissemination of our research findings, in order to strengthen our community involvement and accountability in our activities.

We interviewed Aysha Valery, Senior Assessment Officer in CAR, who supported this project:

Where did the idea for these posters come from? What was their objective?

2023 is the 5th consecutive year that IMPACT – through its REACH initiative – has carried out the MSNA in CAR. During our previous assessments, we often received feedback from communities that REACH is present every year to conduct surveys, but without giving them the results afterwards.

As of 2021, we have therefore started to go out to the locations where we conducted household surveys, to communicate key results to the population through posters, with the aim of using images to make the findings easier to understand – particularly for those who cannot read – with the goal of reaching all sections of the population.

Images are more engaging than a long presentation with figures and humanitarian terminology, which are often difficult to understand for the population, many of whom may not be able to read and write in the predominant language.

Who created the posters, and what was the process?

The posters were created by the MSNA team, which includes the assessment officers, the field coordinators, and the coordination team. First, we discussed which indicators would be the most relevant to people’s experiences. The participation of the field supervisors was essential in this process, as they are the ones who oversee the surveys and data collection and therefore have the greatest knowledge of the communities that we visit. After selecting the indicators, we discussed with a Central African designer, who was recommended by the Working Group on Accountability to Affected People (co-led by UNICEF and OCHA). He then created images of the indicators, making them easily understandable to the population.

How were the posters disseminated to the communities?

The MSNA team, in consultation with OCHA, agreed on the localities to be visited to disseminate the MSNA 2022 results, which were Kaga Bandoro, Berberati and Bangui. Every year, REACH tries to visit new areas to reach communities that have not yet been visited. For us, this also represents an opportunity to raise awareness of what the MSNA is, and to encourage their cooperation.

With the same objective, and in addition to the posters, we established a collaboration with community radio stations for live broadcasts where people can call in to ask questions or interact. The programme is then rebroadcasted in other community relays. Radio stations have also organised after-show listening clubs, which are discussion groups with community members who are registered with the radio station. During these sessions, the posters are presented and discussed with the field supervisors, and then handed over to the community’s town hall for wider distribution. Small posters are also printed for distribution to listening club participants, so that they can disseminate the results in their respective communities.

What was the most important information to communicate about the MSNA?

It was important to explain what the MSNA is, why they’re important, the key findings, and how the data is then used.

On the last point, we collaborated with OCHA which shared how MSNA data is used to plan the humanitarian response. We were also out in the communities with their teams, in each locality, to promote the importance of wider use of data in humanitarian response planning in CAR.

What were the reactions and feedback? Were there any other similar ideas for communicating or exchanging with affected communities?

Reactions were largely positive. Community members expressed their gratitude that REACH had taken the time to discuss the results with them. They also asked for dissemination to local authorities and community members directly, rather than hearing about them through listening clubs.

Turning to the 2023 MSNA and the dissemination of posters, what are this year’s key findings?

After a preliminary analysis of the data, key findings include:

- The security situation seems to be improving, except for the southeast zone where we have seen an increase in armed group activity.

- In many sectors, such as access to water, latrines, health services and protection services, internally displaced persons (IDPs) seem to have more support, due to the concentration of humanitarian actors in displacement sites. According to IOM’s Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM), the number of returnees increased significantly in the first half of the year. Having recently arrived in their places of origin, they need more support to rebuild their lives.

- Regarding mortality, 1 of 16 prefectures demonstrated high crude mortality rates surpassing WHO emergency thresholds during 2023. An additional 6 of 16 prefectures demonstrated elevated mortality rates possibly surpassing emergency thresholds based on their confidence intervals.

- Concerning food security, the situation is critical – 50% of households have a poor or borderline Food Consumption Score (FCS), and most households use ‘crisis’ or ‘emergency’ survival strategies to cope with food shortages (according to the Livelihoods Coping Strategies Index).

- People with disabilities and the elderly seem to have the least access to basic services such as water, latrines, health, and markets.

The results of the 2023 MSNA will be shared soon, with more details on these various figures. Posters will also be created this year, to share the findings with the communities.

All the posters for 2022, by region, can be found below:

- Bangui

- Bangassou

- Bambari

- Ouaka PDI site

- Haute Kotto PDI site

- Kaga Bandoro

- Bria

- Berberati

- Nana Gribizi PDI site

10/10/2023 – Sri Lanka – Evidence-gathering on community perceptions, priority needs, and preferences after one year of humanitarian intervention.

Since the first half of 2022, Sri Lanka has experienced a multifaceted crisis marked by political instability, rampant inflation, and economic disruption, impacting the daily lives of its 22 million inhabitants. In the wake of this evolving crisis, the United Nations Resident Coordinator’s Office (RCO) and the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) initiated a Humanitarian Needs and Priorities Plan (HNP) centred on food security, livelihoods, nutrition, health, and protection.

Now, almost a year on from the initial response, there is a need for a better understanding of how interventions have been perceived by those they aim to support, and to align more closely with the needs and preferences of affected people for future planning. To contribute to this goal, REACH opened an office in Colombo at the start of October 2022 and as part of its first research activities, set out to undertake a broad consultation of affected people and local actors across Sri Lanka. Data was collected using a mixed methods approach with a qualitative focus, and in four case study areas interviews were conducted with persons or groups more heavily affected by the ongoing economic crisis.

The results of these consultations shed light on the deep repercussions of the economic crisis in Sri Lanka. Amongst the varying consequences, households resorted to taking on debt to cope with the shock, and some also reported decreased access to food, healthcare, or medication as a direct impact of the crisis. These challenges not only exacerbated their economic vulnerability but also worsened their quality of life – increasing the need for humanitarian assistance centred on their needs and preferences.

“Due to the current situation in the country, our agricultural activity has been greatly affected. Our income has decreased, and our needs have increased. The reason for this is the shortage of fertilizers and agricultural inputs or equipment in the country.”

Farmer KI (Key Informant) in Kilinochchi

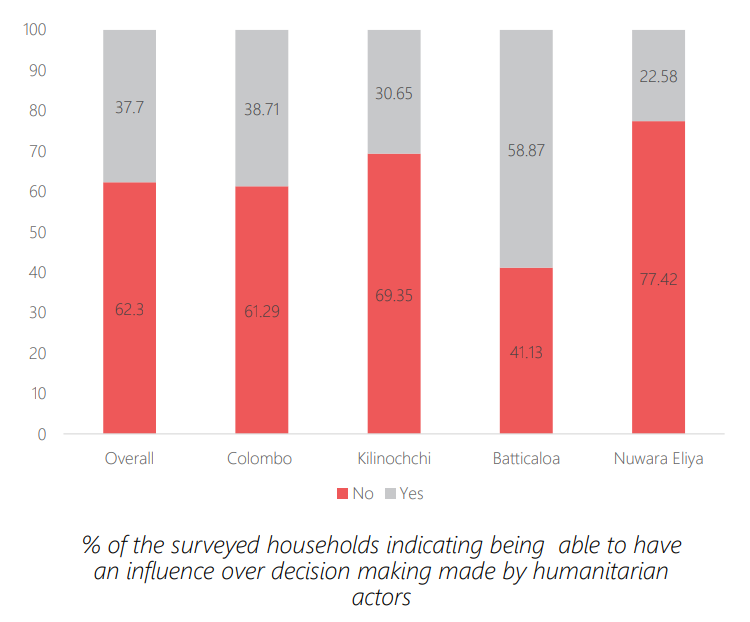

However, the consultations revealed a significant gap in humanitarian assistance delivery, with 69% of households reporting not having received any aid in the 30 days leading up to data collection. Also, while most of the respondents reported being satisfied with the way aid providers behaved in their area, 63% of respondents in Nuwara Eliya reported not being satisfied with aid providers. This discontent stemmed from concerns that humanitarian service providers failed to consult affected populations on their needs, alongside the perception of preferential treatment for certain population groups.

In fact, surveyed households reported favouritism and that communitarian, religious or political differentiations had affected the impartial and efficient distribution of information regarding assistance, and thus the ability to seek assistance. As a result, more than half (53%) of all surveyed households reported that the aid did not go to those most in need. The consultations also underscore the importance of improved information dissemination and increased community inclusion and participation, given that more than half of the respondents were unaware of mechanisms to report issues or engage in decision-making regarding aid.

In fact, surveyed households reported favouritism and that communitarian, religious or political differentiations had affected the impartial and efficient distribution of information regarding assistance, and thus the ability to seek assistance. As a result, more than half (53%) of all surveyed households reported that the aid did not go to those most in need. The consultations also underscore the importance of improved information dissemination and increased community inclusion and participation, given that more than half of the respondents were unaware of mechanisms to report issues or engage in decision-making regarding aid.

These findings highlight the crucial need for aid actors to incorporate the views and perceptions of affected people into future planning and response in Sri Lanka.

Read the full factsheet and presentation.

08/09/2023 – Global – AAP Cross-crisis analysis – Key Messages

Every year, REACH’s Multi Sector Needs Assessments (MSNAs) include several indicators that help to identify trends associated with Accountability to Affected People, including community satisfaction with humanitarian assistance, barriers faced when accessing assistance, and communication needs and preferences.

These themes are complex and can hardly be reduced to simple graphs. Nevertheless, the responses provided by tens of thousands of households to questions associated with AAP can be a good starting point for a broader analysis of priority issues and course corrections – one that should ideally be complemented by in-depth qualitative explorations and local insights at country level. To enable such explorations, we have gathered the core findings from 14 MSNAs in 2022 into a single cross-cutting analysis.

Looking at these results, several points become obvious:

1. Funding matters

Satisfaction with assistance is often highest in responses that are financially well-resourced relative to needs, and lowest in so-called “forgotten” crises facing significant funding gaps. While unsurprising, this serves as a reminder that being accountable to affected people starts with ensuring that funding accurately matches need and, where this is not possible, ensuring that we prioritize limited resources to those most in need. Poorly resourced humanitarian responses lack the flexibility to engage communities in decision-making processes, and to provide quality assistance at a scale that meets needs and expectations.

2. The humanitarian system is unnecessarily hard to navigate

Year after year, and across most countries covered in MSNAs, the primary barrier to accessing humanitarian assistance is simply a lack of information about the assistance that is available. The system tends to respond to this problem by multiplying the channels to communicate with communities, but perhaps there is a deeper problem to resolve in terms of the information that aid actors are truly willing or able to share with aid recipients.

As is it currently set up, the humanitarian system is not designed to enable communities to proactively seek the assistance that they need, for example through systematic and transparent information sharing about the assistance that is available in a given area, the time, date and modalities of registration or distributions, or targeting criteria. This forces people in crises into a passive role whereby there is often little to do but to wait to be ‘targeted’ by humanitarian actors. Communicating better with communities is perhaps first and foremost a question of transparency; therefore moving away from top-down control of information is an integral part of a more accountable humanitarian system. 3. Face-to-face engagement makes a difference

3. Face-to-face engagement makes a difference

For all the promises of digital applications in terms of increasing the scale and scope of engagement between people in emergencies and service providers, it is worth noting that across several countries globally, survey respondents still report preferring to communicate with humanitarian actors directly, ideally face-to-face, to seek information about assistance or to provide feedback. While key opportunities exist for leveraging digital technology to deepen engagement with communities, we should keep in mind that in the midst of an emergency situation, being able to speak face-to-face with an aid worker locally can be a lifeline – one in which we should continue to invest.

Read the full brief detailing AAP findings from the global cross-crisis analysis of 2022 MSNA data.

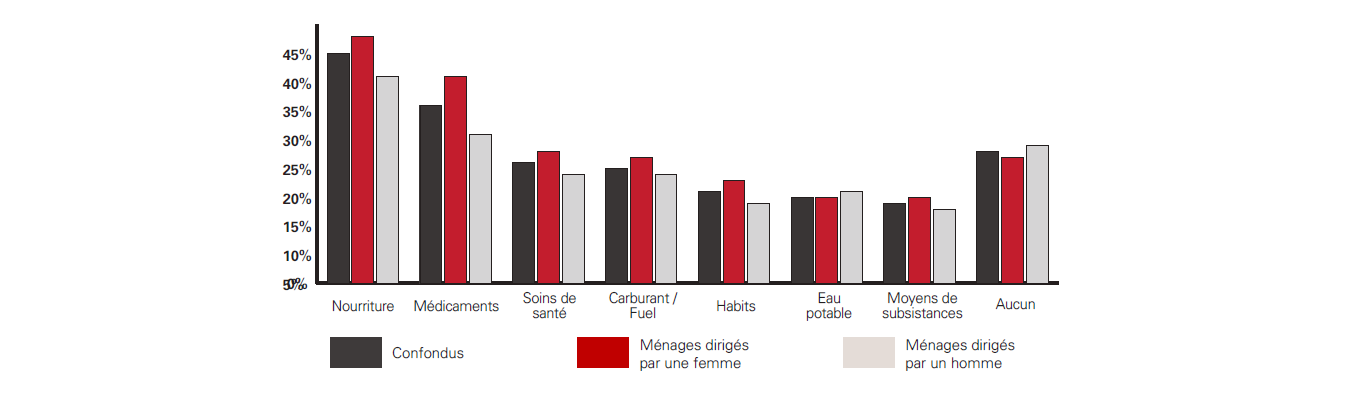

04/09/2023 – Ukraine – Leveraging needs assessment data to understand the gender impact of humanitarian crises: The example of Ukraine.

Since 2016, the platform Convergences has published the “Sustainable Solutions Barometer”, which aims to mobilise all stakeholders in favour of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and to highlight concrete solutions for a more equitable and sustainable world. Produced in partnership with the 1Planet4All project, the Barometer’s mission is to report each year on the efforts being made around the world to achieve a world of Zero Exclusion, Zero Carbon and Zero Poverty. IMPACT contributed to its 6th edition, focused on the fifth SDG on Gender Equality, with an article entitled “Mobilising assessment data to understand the impacts of humanitarian crises depending on gender – the example of Ukraine”.

Humanitarian crises tend to exacerbate pre-existing inequalities within a society, due to the pressure they exert on communities, access to resources, and the respect of fundamental rights. It is thus crucial to consider the impacts of these crises on men, women, and gender minorities. However, with the urgency of the situation and the need for effectiveness in mind, actors tend to favor actions that will benefit the greatest number of affected people, without investigating further the gender-specific impacts of the crisis. This is not to say that gender is absent from collective efforts towards an appropriate distribution of assistance, but the ways gender dynamics are integrated into programming are often based on generic analysis and blanket assumptions rather than a contextualised evidence base.

Humanitarian data collection proves to be necessary to move towards a fair and appropriate distribution of aid. Disaggregating data according to age and gender at an individual level, or according to household demographic composition, helps to produce an overview of the specific impacts of the crisis on these different groups.

After the invasion on Ukraine in February 2022, through our flagship initiative REACH, showed an alignment in household priorities around food and health needs, the differences are tangible in the severity of needs measured. 46% of female-headed households were found to have extreme or very extreme needs in at least one of the sectors of intervention, compared to 38% of male-headed households. This could be explained by different access to livelihoods, persisting discrimination when seeking to access employment, or the wage gap between men and women – existing prior to the war – but could also be correlated with dynamic factors linked to the crisis.

Based on the MSNA, and with the Gender in Humanitarian Action Working Group in Ukraine, the REACH team also collaborated with other humanitarian actors to formulate recommendations tailored to needs resulting from the intersection of different vulnerabilities. For example, while female-headed households aged between 18 and 59 would benefit from support in developing livelihoods and accessing employment, cash assistance appears to be more adapted for households headed by women aged 60 and over.

Quantitative data is indeed essential in supporting the consideration of gender in the humanitarian response, but it is also crucial to identify grey areas persisting beyond statistics. Needs assessments tend to focus on the impacts of an immediate shock, whereas gender inequalities are the results of normative, institutional, and social processes that are harder to quantify.

| “To address these more complex problematics, quantitative assessments need to be completed by contextualised analyses, more targeted research, and a close collaboration with actors from civil society – to promote an inclusive humanitarian response that considers gender dynamics.” – Cosima Cloquet, IMPACT Gender & Inclusion Assessment Specialist. |

Read the full article here, starting on page 11.

IMPACT will be at the 15th edition of the 3Zero World forum in Paris on 5 September – come visit our booth if you have any questions.

19/08/2023 – Burkina Faso – Piloting an accountability monitoring tool in Burkina Faso

With the aim of strengthening the participation of crisis-affected communities in humanitarian decision-making processes and programming in Burkina Faso, IMPACT – through its flagship initiative REACH – worked with partners to pilot an accountability monitoring tool in the city of Fada N’Gourma.

As said by Jean Valéa, Humanitarian Affairs Officer for UN OCHA and one of the key project’s partners, “You can’t serve people that you’re not listening to”. For Accountability to Affected People (AAP), it’s crucial to assess how humanitarian organisations report back to affected communities and how their observations and feedback are taken into account – to allow the review and adaptation of aid actions if needed.

Overall, this is exactly what the project aimed for: to develop a tool that effectively increased community engagement in designing humanitarian assistance, assessed how aid is received and perceived, and reviewed existing complaint and feedback mechanisms.

For this project, developed in partnership with Fonds Humanitaire Régional pour l’Afrique de l’Ouest et du Centre (FHRAOC) and OCHA, household surveys, focus group discussions, and Key Informant (KI) interviews were conducted from January to February 2023. These tools were developed through consulting the local Community Engagement and Accountability Working Group (CEAWG), with whom the results from the pilot study were also jointly analysed. The last step of this project was to train local humanitarian partners from the CEAWG on how to use these pilot tools, with the objective of sustaining the monitoring mechanism over the longer term.

In addition to building the capacity of local actors, the REACH team wanted to broadcast to the local population and other interested actors about the importance of promoting accountability in humanitarian action, which was done through a radio talk show and a documentary. We partnered with the local radio station Tin Tua to broadcast a discussion with the REACH Field Officer in charge of the data collection, as well as local representatives in the local language Gourmantche.

A local film company, Fama Film, also created a documentary presenting the different stages of the project, from data collection in communities, to communication of results through the radio talk show, to the trainings held for partners. The documentary also highlights relevant stakeholders’ views on the advantages of the accountability mechanism and what this project means for the humanitarian community.

Key takeaways from the project

The evaluation revealed a difference in perception between households and humanitarian actors on several key points about accountability and community engagement.

For example, the study found a strong perception among respondents that humanitarian assistance was denied to many with self-reported needs: although most of the humanitarian actors interviewed as KIs did not report the existence of barriers to accessing assistance, 65% of households indicated exclusion from targeting as the main barrier to accessing assistance for at least one of their priority needs. Similarly, while KIs felt that satisfaction with assistance was high, 41% of households who had received assistance reported they were not satisfied with the quantity of aid they received.

Regarding two-way communication, although humanitarian actors had reportedly assured communities that they would be consulted, only 28% of households reported actually having been consulted in the six months prior to being interviewed. Similarly, it was found that only a third of surveyed households reported being aware of complaint mechanisms.

The study also touched on more sensitive topics such as beneficiary selection criteria and fraud, or other cases of mishandling by humanitarian agents. Enumerators who led these discussions, mostly through focus groups, were carefully trained and sensitized to issues such as Preventing Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (PSEA). While focus group participants revealed a certain degree of compliance with exchanging money for aid in three quarters of the groups, they also advocated for the need to combat fraud by enforcing a stricter code of conduct among aid workers and raising awareness among vulnerable populations.

Next steps

Following the project, IMPACT will continue to support our partners within the CEAWG in replicating the evaluation in the other regions they work in. By doing so, they can reinforce their engagement with the communities they serve and ensure that they are actively measuring their actions against their own accountability commitments. IMPACT will reflect on how the project’s learnings could potentially be applied and scaled up outside of Burkina Faso.