Afghanistan: Displaced children face higher risk of child labour and marriage

9 February 2018

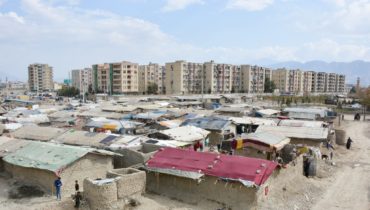

As the protracted conflict continues throughout their country, the people of Afghanistan find themselves subjected to widespread displacement for a fourth consecutive decade. With more than 350,000 people newly displaced in 2017, the living conditions and well-being of displaced populations continue to fall, with overcrowding, decreased access to services and prevalent use of negative coping strategies becoming the norm. These vulnerabilities and concerns affect all members of displaced households, including girls and boys, with poor education attainment and protection vulnerabilities becoming an ever increasing concern.

Given the sensitive nature of education and child protection concerns within Afghanistan, existing data typically focuses on specific geographical areas or particular population groups. To address this information gap, REACH collaborated with OCHA and the Education in Emergencies Working Group (EiEWG) to develop the Joint Education and Child Protection Needs Assessment, with data collected in August and September 2017. This assessment provided full geographical coverage across all six of Afghanistan’s regions, and included a range of displaced population’s perspectives, resulting in 9,435 household level interviews in addition to 18 focus group discussions with purposively sampled teachers and community leaders.

Overall, findings highlight that conflict and displacement worsen education attendance and use of negative coping strategies, such as child labour and marriage, indicating extensive protection concerns throughout the country. In particular, displaced children face exacerbated barriers to education, resulting in 23% of displaced children remaining unenrolled in school. Furthermore, of those that are enrolled, 36% of girls and 22% of boys do not regularly attend school. Exacerbating these vulnerabilities, REACH found that few schools provide the necessary psycho-social support and well-being services to meet the needs of displaced children, with 96% of households reporting no such services within schools attended by their children. However, it was found that teachers provide a strong level of support, encouraging open discussion. Thus a key recommendation from this assessment is to promote the capacity building of teachers across Afghanistan to improve the psychological well-being of displaced children.

Given the surprising findings of this assessment, discussed extensively amongst the humanitarian community in Afghanistan, and the implications this has for education and child protection programming, REACH recommends that further research on the changes in school enrollment following displacement takes place, in order to further strengthen decision-making by humanitarian actors to provide effective programming throughout the country.

Access REACH’s Joint Education and Child Protection Needs Assessment in full at this link.