Three key ways global decision-makers can support humanitarian workers in delivering on AAP

19 August 2022

Each year, 19 August marks World Humanitarian Day (WHD), designated by the UN General Assembly seven years ago as a day to commemorate aid workers, to advocate for their continued safety and security when deployed in fragile contexts, and to advocate for action in support of the millions of crisis-affected people around the world.

WHD can serve as a reminder to all actors across the humanitarian system on the importance of accountability – to ourselves, to the core humanitarian principles, and to the people we are meant to assist. This year, we look at recent findings from our country teams and reflect on three key ways global decision-makers can support humanitarian workers in delivering on their Accountability to Affected People (AAP) commitments.

- Empower – and learn from – local humanitarian actors.

Providing more support and funding tools for local and national responders was a core commitment in the 2016 Grand Bargain; recognising that there was more work to be done on this front, five years later, Grand Bargain 2.0 also put localisation at the centre of its priorities.

Local responders offer a wealth of knowledge about the crisis context and the people affected, and often have access and operational capacity in areas where international actors need more time to build a presence. For example, in occupied or direct conflict areas of Ukraine such as Kharkiv, our research found that local civil society organisations (CSOs) and volunteer networks were best positioned to identify needs and deliver assistance. In many cases, CSOs were able to deliver food, medicine, and hygiene items directly to homes – ensuring people’s access to vital assistance. To ensure their sustainability, however, direct funding support from institutional donors was needed earlier on, especially for organisations operating front-line response through volunteers. Taking another example from Ukraine, local actors have shown the way in terms of communication with communities and using social media networks to ensure access to information about humanitarian assistance – aspects of the response where international partners were lagging behind in the first weeks and months.

Settlement-based approaches are another key way in which local actors can be empowered, particularly during the stabilisation and recovery phases of a crisis. In Niger and Central African Republic (CAR) for example, the AGORA approach facilitated collaboration between local authorities and humanitarian actors in the development of contextualised and territory-specific local recovery plans. Often excluded from response planning by international organisations, the collaborative workshops in these two countries helped put local actors – and their knowledge about isolated and hard-to-reach communities – at the centre.

- Enable quality assistance through adequate funding – especially in protracted and “forgotten” crises.

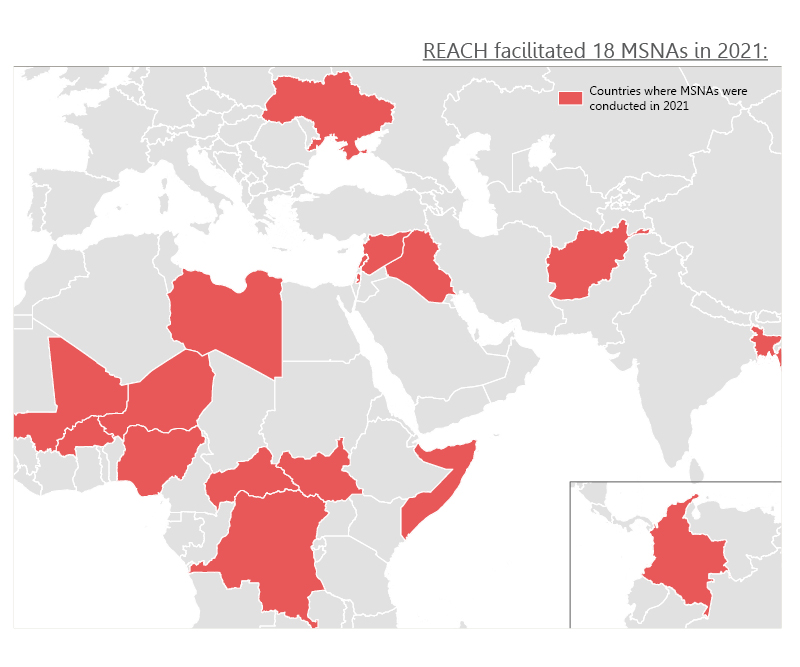

AAP data collected by REACH across 12 countries in 2021 found persisting dissatisfaction with humanitarian assistance among recipients of aid in several contexts, including high levels of dissatisfaction in a number of protracted crises such as South Sudan, Mali, and occupied Palestinian territory. When asked to cite primary reasons for dissatisfaction with humanitarian assistance, households generally noted inadequate quantity of assistance available, followed by issues with quality of aid, and delays. Looking at South Sudan in particular, where dissatisfaction was reportedly highest, interviewees noted that the assistance they received did not adequately cover their needs.

In many cases, aid actors are constrained by resource gaps, as annual funding envelopes begin to decline the longer a crisis endures. As of mid-June, only 20% of funding requirements through the 2022 Global Humanitarian Overview have been met. In the central Sahel, coverage is even lower – 15% of the appeal has been funded in Burkina Faso and Niger, and only 11% in Mali. Although global attention in contexts like these fades over time, it is critical to ensure that prioritization of funding is tied to where the evidence shows needs are highest, and not where media coverage or general public interest may fall.

- Ensure resourcing and meaningful operationalisation of collective accountability mechanisms.

Given these funding shortfalls, it is no surprise that in resource-constrained responses, operationalising collective accountability mechanisms may be deprioritised. However, investing in two-way communication and robust community consultations as part of the Humanitarian Programme Cycle can bolster more accurate targeting of needs and greater satisfaction with aid among affected people in the long term.

Turning again to our global analysis, in a number of contexts, we found significant proportions of households reporting that they were not consulted on their needs and preferences regarding aid – highest in CAR, Niger, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and Bangladesh host communities. In South Sudan, interviewees noted a perceived lack of inclusion among certain groups in the consultation process, such as women, older people, and people with disabilities, reflecting a wider exclusion from community level decision-making processes. In many of these same places, awareness of complaint and feedback mechanisms was also low. Donors can play a key role in supporting the meaningful implementation of collective accountability mechanisms, by putting these approaches at the forefront of their agendas and requiring AAP mainstreaming to be a core consideration in all humanitarian interventions.